Floundering About in Spanish

So here I am in Argentina, floundering about in Spanish. I knew this would happen. It is a Spanish-speaking country, after all. Still, it is one thing to know a thing and another to plunge into the reality of that thing.

And the reality of the thing is that I have good Spanish days and I have bad Spanish days. Good Spanish days are ones where I don’t have to apologize for butchering the language too many times, and am only infrequently forced to utter the words no entiendo (“I don’t understand”).

There are even occasional triumphant Spanish days, but these are so rare I can remember all three of them: that visit to the hairdresser and a meaningful, mutually intelligible hour-long conversation. That taxi ride attended by a similar miracle. The driver and I talked non-stop. In Spanish. We were both sorry when it was over. Oh what a triumphant Spanish day that was! And that brief encounter when a man sprang forward to catch me as I stumbled on the uneven pavement, the sort of gallant reaction I have come to expect from the people of Buenos Aires. As I righted myself he made some quip, of which I got the gist, about a scene from a movie where the heroine quite literally falls into the hero’s arms. Pero la vida no es una pelicula, desafortunadamente, I replied, before floating away on a cloud of pride at my tiny linguistic triumph, which in this case came after, and not before the fall.

All the rest, which is most of them, are under the category of bad Spanish days. On bad Spanish days I forget everything I thought I knew about Spanish. On bad Spanish days I am gifted with discouraging insight into my inability to remember simple words and phrases, let alone conjugations (and Spanish has a lot of those). Bad Spanish days are humbling, but humility is good for the soul, I believe, for it prevents us getting above ourselves.

You may be familiar with the myth that Spanish is just about the easiest language in the world to learn. I can attest to the first part of that sentence: it is indeed a myth. For Spanish is a highly sophisticated, gendered language with about 3000 tenses. Slight exaggeration—it actually has eighteen. But when you factor in the four “moods,” among which lurks everyone’s nemesis, the subjunctive, and multiply the seven different endings—first person singular/plural, second person singular/plural, formal and informal versions of the second person etc.—it adds up to about 126 ways to utter a single verb, which means there are 125 possible ways to get just a single word wrong.

Cooking the Poncho

But before I start mangling the endings, I first have to remember the verb itself. I still cringe about that expedition to Once, the iconic fabric district of Buenos Aires (pronounced Onsay), and the moment I confidently informed the shopkeeper that with the fabric I was buying, I was going to cook a poncho.

I only realized my mistake—that I’d muddled cocinar (to cook) with coser (to sew)—on the bus home, clutching the bag of fabric supposedly destined for the cooking pot and mentally replaying my Spanish encounters of the day. For this is what I do, and I do it in the hope that I will discover I have just had a tremendously good Spanish day. That has only happened three times, though, so perhaps I should stop.

Nevertheless, the people of Buenos Aires are exceedingly gracious. No-one has ever made me feel worse about my Spanish than I already do. In fact, they are more likely to apologize for not speaking English than laugh, or scoff, or get annoyed. This is most generous of them, seeing it is their country not mine, and unlike me, they have no obligation whatsoever to speak to me in a language other than their own.

I have also discovered the value of improvisation in achieving mutual understanding. So, the other day when I found myself in need of some stock cubes with which to cook the poncho, and didn’t have the faintest clue what the word for “stock cube” might be, I improvised. “Do you have chicken stock cubes?” turned into “Do you have those small square things that you put in chicken soup?” It was a convoluted construction accompanied by a finger drawing of a small imaginary cube, and the miming of a crumbling action, but it did the trick.

“Over there,” said the shopkeeper, who understood immediately. And there they were. Between the jam and the biscuits and not with the savory stuff, which is where you would expect to find them, and the reason why I had to ask at all. But this is Buenos Aires, which has a logic all of its own, although I’ll save that particular rabbit hole for another time.

Along with averagely bad Spanish days, there are also truly terrible Spanish days. Terrible Spanish days generally involve a phone call. These are terrible because in a phone conversation there are no hand gestures, shrugs, smiles, and imaginary stock cubes to fall back on. I did not appreciate the importance of the body until I had to communicate daily in a language I am very bad at.

So I psyche myself up for the dreaded ordeal, and it is always an ordeal. I look up potentially helpful key words: “broken,” “flooded,” “urgent,” “desperate,” etc. and practice my opening sentence. This is a mistake, because the disembodied voice at the other end of the line thinks s/he is talking to someone who can actually speak Spanish, and responds with a volley of words uttered at machine gun speed. I flounder; ask him/her to repeat him/herself, and finally admit in faltering Spanish that I don’t speak Spanish very well, hardly at all, in fact, and does s/he by any chance speak English? No? Oh dear. Time to hang up.

Machine gun speed speech is a widespread problem, mind you, and affects face-to-face encounters also. If only the good people of Buenos Aires spoke more slowly, or moved their mouths when they spoke. Or didn’t swallow the letter S. Or all three of those.

Relearning Everything

There’s an added complication. I am by no means the first person to arrive in Argentina thinking I can understand and speak a little Spanish, only to discover that I neither understand nor speak it the way it is spoken here. The reasons are complex. Thanks to a heavy migrant influence, Argentine Spanish has the same intonation as Italian. Then there are various peculiarities and variations to do with pronunciation. And with verbs. But most of all with words and expressions for common objects and concepts. There is a whole other Argentinian dialect that overlays the Spanish held in common throughout the Spanish-speaking world, and it is known as Lunfardo. This highly distinctive dialect had its origins in the prisons of Buenos Aires in the late nineteenth century, I believe, and from prisoners’ efforts to confuse their jailers by speaking in ways that would not be understood. In some cases this was achieved by substituting words imported from other languages: Italian and Portuguese, for example. In others, it involved saying Spanish words backwards. So, for example, pagar (to pay) became garpar, la noche (the night) became la cheno. The confusion is still working.

So, not only do I have to relearn intonation and pronunciation, I also have to learn new words for Spanish words I already know, and I have to learn to say words I already know backwards. I have enough trouble saying them forwards.

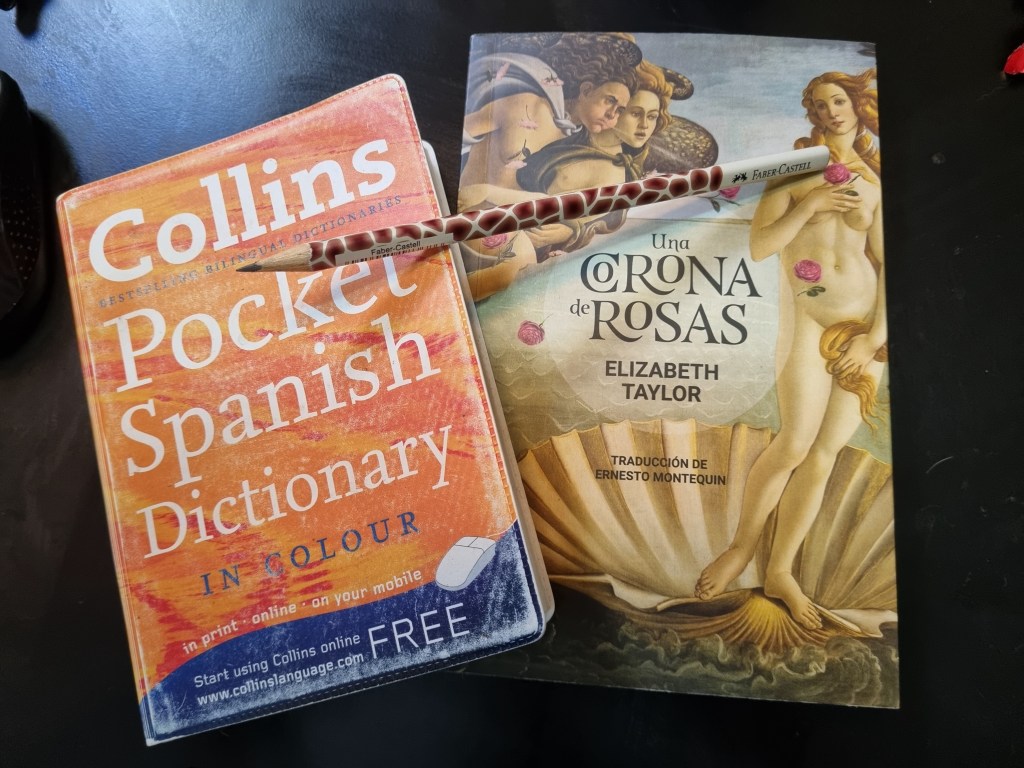

So, no, I haven’t mastered neutral Spanish yet, far less the idiosyncratic Spanish of Argentina, but I have become something of an expert on the many resources for Spanish learning out there on the world wide web. I’ve tried most of them, and in a future blog I will provide a comprehensive review that might be helpful for other Spanish learners. But for now, and in closing…

The Illusion of Progress

Internet resources for Spanish can be divided into categories, and the first of these I call the Illusion of Progress. Taking prime place in this category has to be the cleverly-gamified, grammar-lite and highly popular Duolingo, with its annoying cartoon characters, robotic voices, and meaningless bonuses and rewards designed to keep you hooked in. I wasted an inordinate amount of time on Duolingo, thinking I was learning Spanish.

Then there is the category Worthy but Excruciatingly Boring. I won’t bore you with details for now, except to say it is quite a large category.

The Plain Worthy category is also extensive. I have learned a great deal from websites and so forth that fall into this group. They are all useful, especially if used in conjunction with other worthy resources. SpanishDictionary.com is number one here. I still use it daily, mostly for the all-important built-in dictionary, but it has lots more besides: videos, lessons, exercises, and none of them too excruciatingly boring.

There is one resource that merits a category all of its own, and this I call Unintentionally Hilarious. The sole occupant here is a slightly updated version of a Spanish language course put out by the American Foreign Service Institute sometime in the last century. (There may be others, and if you know of any, do please let me know in the comments below.)

Originally aimed at diplomats preparing for service in embassies and consulates in Spanish-speaking countries, Unintentionally Hilarious is riddled with stereotypes and unselfconscious racism. The lessons are built around dialogues featuring our hero, a mid-level diplomat who has just arrived in some unspecified Latin American country. El Senor John White (the clue is in the name), then has encounters with an array of locals, in which we hear him instructing waiters with commands like “Boy! Fetch me a beer!”; demanding cleaning ladies accept less money than is decent for the honor of cleaning his apartment; and outsmarting taxi drivers who have had the affrontery to try and overcharge him.

But the winning category, although I suspect it might in fact be a close cousin of Illusion of Progress, is the one I call Addictively Fun. This is movies and soap operas in Spanish, basically, stuff that is available on Netflix and similar platforms. Some are truly wonderful. Others are dreadful, but nevertheless addictively fun. Which is is probably why, although I am 104 episodes into Montecristo, an Argentine production very loosely based on Alexandre Dumas’ epic novel, I am unable to dismiss the niggling suspicion my Spanish is no better than it was 103 episodes ago. Still, as self-deception goes, I daresay I could do a lot worse.

Which reminds me— I only have a week before my Netflix subscription expires, and there are thirty episodes to go before Montecristo reaches its melodramatic conclusion, so there’s important Spanish learning work to be done.

Leave a reply to Mathew A Vadas Cancel reply